About

Shaolin M.A.T.C.

Master Jason Knapp

I started training in February of 1995 under Senior Master Jim Mooney at the Salvation Army gymnasium. When I became a blue belt Senior master Jim turned the class over to his son Master Jamie Mooney. Master Jamie has been my instructor ever since. The school moved to the Jim Spence center in St. Mary’s and then to our first dedicated location in Williamstown then to our current location on Rosemar road in Parkersburg. Master Jamie turned the school over to me 14 years ago, when he moved to Columbus. In my 22 years of training I have fortunate to be able to learn from Grandmaster Sin Kwang The, the head of our system, and Elder Master William Leonard as well as Elder Master Gary Mullins. I have cross trained with Grandmaster Dale Brown in traditional Japanese Jiu-Jitsu, Sensei Terraun Jones and Rob Moat in American Jiu-Jitsu, Judo, and Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. In studying other styles and systems I find I learn more about Shao-Lin. I try to learn as much from my students as I impart to them. True learning comes from an open mind and seeing things with a beginner’s mind.

The History of Shao-lin

The Legend of Bodhidharma

Ferociously ugly, with piercing blue eyes and wild curly hair, the Indian monk Bodhidharma is known as the founder of Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism and of the Shao-Lin fighting arts. Sometime around 500 A.D., Bodhidharma traveled by ship from southern India to eastern China. He traveled hundreds of miles, crossing the Yangtze River and the Himalayan mountains, eventually finding his way to the Shao-Lin temple in the Honan province. When the monks would not admit him, he went to a nearby cave and meditated for 9 years, finally boring a hole in the wall of the cave by the fierceness of his gaze. With this feat, the monks admitted him to the temple, and he taught them his direct, meditation-based form of Buddhism, which involved long hours of sitting still. But he found that the monks were weak, unable to withstand the pressures of static meditation, so he taught them breathing exercises and physical techniques which eventually gave rise to Shao-Lin Kung Fu as we know it today

The Shao-Lin Temples

Many of the monks in the Shao-Lin temple were retired soldiers and generals. Under the pressure of frequent attacks by bandits, the Shao-Lin monks combined Bodhidharma’s teachings with the martial arts techniques of the Chinese warrior class. The development and refinement of these combined techniques gave the Shao-Lin warrior monks an almost unbeatable edge, and a far-flung reputation for martial arts prowess and fighting abilities. The Fukien temple became the second temple of Shao-Lin around 650 A.D. Through the centuries, the fortunes of the Shao-Lin monks rose and fell with the political and dynastic changes of Chinese history, and gradually, other temples became part of the Shao-Lin system. With their superb fighting skills, the Shao-Lin were alternately courted and renowned by those in power who wished to have the monks on their side, or vilified and suppressed when those who feared them came to power. The temples were burned and rebuilt, burned and rebuilt, but the knowledge of the monks survived while they continually added to and improved upon the techniques.

For the most part, the temples prospered and became widely known as centers of learning and philosophy as well as of the martial arts. Gaining admission to the temple was difficult. Young students were expected to wait outside the temple for what must have seemed an eternity while their temperament and attitude was observed by the monks. Once admitted, they endured years of service and menial chores before being accepted as disciples. Once accepted, they would receive an unparalleled education in philosophy, fine arts, and the martial arts. In order to graduate from the temple, they had to exhibit phenomenal skills, and pass through 18 testing chambers. If they survived the first 17 (and there were those who did not), they would have to grip a burning-hot iron cauldron with their bare forearms, which would brand them with the raised relief of a tiger and a dragon.

For hundreds of years, the Shao-Lin masters developed new styles and forms of training, bringing back to the temples variations and innovations in the martial arts that they had encountered in their travels. Their arts flourished in the temples during the Ming Dynasty. But this golden age was not to last. In the mid 17th century, Manchurian invaders began to systematically and brutally take control of China. Internal rebellion contributed significantly to the fall of the Ming Dynasty, and the betrayal of an insider was the cause of the almost utter destruction of the Honan temple in 1647 A.D. Many monks fled to the Fukien temple, where they continued to support the resistance fighters. This, in turn, led to the destruction of the Fukien and other temples and the outlawing—punishable by death—of the practice of Shao-Lin Kung Fu. Outlawed, the Shao-Lin continued to teach in hiding and in exile. It took over 100 years before the temples were reopened around 1800, but only for religious purposes. The disastrous Boxer Rebellion of 1900 caused another wave of escaped resistance fighters, many of whom were Shao-Lin monks. They scattered to the United States, Australia, Korea, Indonesia, and other countries. The third burning of the Shao-Lin temple happened in 1927. In recent years, the government of China has come to realize the importance of the cultural heritage of Shao-Lin, and reopened the temples.

The Grandmasters

The Shao-Lin schools under the Shao-Lin Grandmaster Sin Kwang Thé trace their lineage back to the Fukien temple through a succession of three remarkable Shao-Lin Grandmasters.

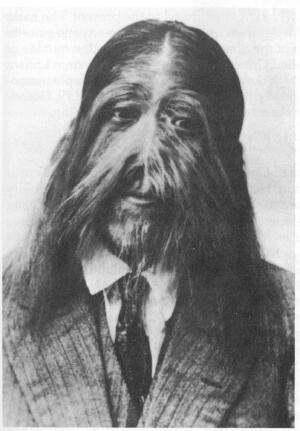

The first of the three Grandmasters was born in Fukien in 1849. He came in to the world covered with hair from head to toe. His horrified parents, convinced that they had given birth to a demon, abandoned the infant in a forest near the Fukien Temple. A passing monk rescued the newborn and presented him to the Shao-Lin Masters. The Masters realized that it would be nearly impossible to find a family willing to adopt such a child, so they decided to raise him themselves. They named him Su Kong T'ai Djin.

From childhood on, Su Kong T'ai Djin studied the Shao-Lin art with exceptional dedication. The Fukien Masters responded to his enthusiasm with a rare variance from Shao-Lin tradition. Instead of assigning Su Kong's training to a single Master, as was the practice, each of the Fukien Masters contributed to Su Kong's martial education. Su Kong was therefore able to complete every branch of Shao-Lin training, learning and mastering hundreds of forms and disciplines. It was an unparalleled achievement. [Usually the 10 Grandmasters of the temple each learned 1/10th of the Shao-Lin art].

Su Kong's knowledge and strong character led to his appointment as the Grandmaster of Fukien. More than once, his exceptional martial skills were needed to fulfill the responsibilities of his position. For example, he once arranged a meeting with 12 Shao-Lin Masters, representatives of the Shao-Lin Temples of China. When Grandmaster Su entered the room for the meeting, all the Masters bowed. Instead of returning the bow, Grandmaster Su picked up a knife and threw it up the rafters. An assassin tumbled down from his hiding place, the knife embedded in his heart. Grandmaster Su had heard 13 men breathing where there were only supposed to be 12!

The Fukien Shao-Lin monks took it upon themselves to protect the Fukienese coast from the raids of Japanese pirates. They were tremendously effective, earning the love and respect of the common people. When word reached the Ch'ing Kwang Hsu Emperor in Peking at the beginning of the 20th century, trouble brewed. Kwang Hsu saw the Fukien monks as potential rebels with widespread popular support. He secretly dispatched imperial troops, armed with cannons on a mission to destroy the Fukien Temple. He even sent a renegade Shao-Lin Master, Chi Tao Su, the White Eyebrow Monk, to strengthen the attacking force. A sympathetic official warned the monks of the impending attack. The Fukien Masters chose a surprising, ingenious solution. They evacuated the Temple, removed all of its valuable artwork and books, and set fire to the temple themselves. They hoped to rebuild the Temple in more favorable times. More favorable times never came.

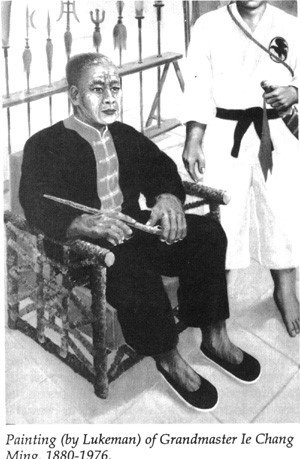

Grandmaster Su and his disciples retreated into the Fukienese mountains to continue their training. One of the disciples was Ie Chang Ming, the man who would become the second of the three Grandmasters of our lineage. Su Kong died in 1928 at the age of 79. Ie Chang Ming was born in 1880. He was admitted to the Fukien Temple as a small boy. Like Su Kong, Ie Chang Ming poured all of his time and energy into the martial arts training, especially the Golden Snake style. Tied hand and foot, he could evade spear thrusts by twisting and turning like a snake. He could also wrap his body around a pole climb it, like a snake on a vine.

Grandmaster Ie's extensive knowledge, sensitivity, and martial skill was complemented by great personal strength and concentration. For example he trained wearing a weight vest (equal to his body weight!), and used an iron staff and Kwang Tao. He also did the Iron Bar posture (stretched out between two wooden benches, with his head on one bench and heels on the other) for 2 hours every night.

One evening, while traveling through the countryside, Grandmaster Ie took a shortcut through what appeared to be an abandoned military encampment. Although the camp was almost deserted, it was not abandoned. A sentry stopped Ie. Soon other sentries appeared, bringing the number of soldiers to 11. They taunted Ie, and became increasingly aggressive. When they ordered him to lick their boots, Ie knew he had to take action. All 11 soldiers were killed in the resulting fight.

A price was put on Ie Chang Ming's head. He escaped to Indonesia, settling in Bandung, where he eventually established a Shao-Lin school. It was not easy to become his student; there was a long waiting list and each prospective student had to prove his/her worthiness.

In 1943 a boy named Sin Kwang Thé was born in Bandung who would one day become the third Grandmaster of our lineage. His family had several Shao-Lin ancestors and young Sin was drawn to the martial arts. His father, however, had been injured during martial arts training when he was a young man and opposed his son’s wishes. Nonetheless, Sin Kwang's mother secretly let him out a 4 am each morning, so that he could study the martial arts. He began with sand burn training. Sand burn training is a crude form of toughening the hands by thrusting them into buckets of hot sand.

After 6 months, the sand burn man stopped teaching. Sin Kwang heard about Grandmaster Ie's school and went to watch. Grandmaster Ie had 80 students practicing empty hand forms, weapons forms and sparring. The 7-year-old Sin Kwang asked to join the school, but he was put off with polite excuses. One evening, Grandmaster Ie spilled a bowl of uncooked rice on the training hall floor.

He asked Sin Kwang to pick up the rice, grain by grain, and to blow the dust of each grain. He was to find all of the 855 grains that had been in the bowl. It was late at night, and the Shao-Lin students had all gone home, by the time Sin Kwang was through dusting and counting the rice. The rice counting was only the first of many tests of determination and character Sin Kwang passed. For the final test, Ie spilled hot tea on the boy and took hold of him, looking deep into his eyes. He saw no anger, only surprise. Sin Kwang Thé was finally accepted as a Shao-Lin student. In the beginning, Grandmaster Ie had Sin Kwang do hundreds of squats to build up his legs. They were done standing on the edge of a chair, with only the balls of his feet touching the seat. He also had Sin Kwang stand in horse stances for what seemed like an eternity. Next came mastering all 49 postures of the I Ching Ching. Only after these preliminaries were completed, did training in martial techniques begin. Five years later at the age of 13, Sin Kwang Thé tested to Black Belt. For his test, he had to spar 7 other students while blindfolded. He also had to do forms blindfolded. At different times during the forms, boards were held in his path. Since he didn't know when there would be a board, every strike in every form had to be true.

In 1964, Master Sin was preparing to go to Germany to study engineering and physics. He had added German to the multitude of languages that he could speak. Yet the Berlin crisis altered his plans. By chance however, he met a couple from Lexington, Kentucky who were able to arrange a scholarship in the US for him. Master Sin Kwang Thé came to the United States. Master Sin studied academic subjects with the same dedication that he gave to the Shao-Lin art. As often as he could, he returned to Indonesia, for the time had finally come for him to learn the Golden Snake Style.

First of all, Master Sin had to learn to move like a snake. Grandmaster Ie tied Master Sin's wrists to his feet in an arched position similar to the I Ching Ching #35 posture. In this position, he learned to crawl by moving the muscles of his chest alone. Grandmaster Ie also threw Master Sin into the ocean with his hands and feet tied. Master Sin learned to swim by wriggling his body. Only now was he ready to learn the Golden Snake forms.

In 1968 Master Sin's training was complete. Grandmaster Ie awarded him the 10th Degree and the Grandmaster's Red Belt. Sin Kwang Thé had become the youngest Grandmaster in the history of the Shao-Lin art.

Grandmaster Thé continued his education and was on the verge of completing his Master's Degree when Ie Chang Ming died at the age of 96. Grandmaster The realized that while there were many engineers and scientists, he was the only Shao-Lin Grandmaster. He dropped his studies in order to devote all his time to teaching the Shao-Lin art. Shao-Lin Grandmaster Sin Kwang Thé could have returned to Indonesia to resume teaching the art. Instead he chose to stay in the United States. This was a bold break with tradition, for in the past only full-blooded Chinese had been permitted to learn the Art. Yet when American men and women from all walks of life were able to learn what was once taught to a handful of Chinese monks, it was clear that martial arts excellence depended on time and effort and not race. There are now several American Masters.